De la misma manera, se han pretendido y se pretenden cambios sociales encaminados hacia determinados ideales o como reacción en contra de las circunstancias actuales.

Todo ello supone una transmutación, ya que se pretende cambiar la mente y la ideología de millones de personas para que se produzca un cambio social controlado y en determinado sentido.

Annie Besant fue notable como activista política para que la India se emancipase del Imperio Británico antes de que aceptase el cargo de presidenta de la Sociedad Teosófica, influyendo profundamente en seres que como Gandhi, han dejado una cuña de valores espirituales inmersos en un clima de odio y de materialismo, lo que provoca contradicciones que se manifiestan en la destrucción o en el deseo de destruir, retrasando la expresión objetiva de aquella energía espiritual y cohesionadora.

Dentro de estas iniciativas, colectivos como la Sociedad Teosófica o la Golden Dawn, surgieron en el siglo XIX como resultado de los grupos de pensadores, místicos y políticos que se encontraban desencantados ante dos siglos de racionalismo, época descrita por el poeta irlandés William Butler Yeats como: “la rebelión del alma contra el intelecto”.

Pues tanto Escocia como Irlanda, fueron alentadas por personajes como Yeats para llevar a cabo sus aspiraciones independentistas y tratando de encontrar en sus raíces celtas todo aquello que justificase sus motivos para emanciparse.

En Gran Bretaña, la Golden Dawn influenciaba a autores de novelas como el mencionado Bram Stoker o Bernard Shaw, mientras que en Francia se producía una potente corriente dentro de la que se encuentran personajes como Alejandro Dumas, George Sand, Delacroix, Poussin, Gerard de Nerval o el mismo Jules Verne, y esta corriente la provoca la Sociedad de la Niebla.

Esta sociedad se fundó en el siglo XVI por un impresor afincado en Lyon y llamado Griphe para la que eligió el nombre de “Néphès”, una antigua sociedad griega cuyo nombre significa “niebla” y constituye el símbolo sobre el que se representa la acción de Dios en el mundo, tal como se contiene en el libro Eclesiastés, 24-4: “Yo levanté mi tienda en las alturas y mi trono era una columna de nube”.

Y esta acción de Dios en el mundo la pretenden realizar a través de iniciativas como las de estas sociedades provocando cambios sociales desde las mentes de los hombres.

La Sociedad de la Niebla toma su ideología de la francmasonería y, al menos en sus principios, pretende el conocimiento de Dios a través de la naturaleza y de sus leyes reproduciendo la filosofía natural aristotélica, ideología compartida asimismo por los gnósticos y rosacruces, resultando que la mayor inspiración de la Sociedad de la Niebla la encuentra en Los Iluminados de Baviera, sociedad creada por Adam Weishaupt en el siglo XVIII y que, según George Sand, reclutaba a todos los instigadores que: “dirigen todas las cosas, deciden la guerra o la paz, castigan a quienes consideran perversos y hacen temblar a los reyes en sus tronos”.

Curiosamente, los Iluminados de Baviera defienden los ideales de Libertad, Igualdad y Fraternidad, habiendo influido decisivamente en el advenimiento de la Revolución francesa en 1.789.

La Sociedad de la Niebla rehabilitó un texto medieval atribuido a un monje dominico en Italia, Francesco Colonna, siendo el nombre del libro “El sueño de Polifilo”, con contenidos que han influido a Miguel de Cervantes, Dante y Goethe, y han inspirado jardines como los de Versailles en Francia, los de Bomarzo en Italia o los de Aranjuez en España, todos ellos llenos de símbolos descritos en El sueño de Polifilo.

Alejandro Dumas, padre, publicó en 1.839 su novela “El Capitán Panfilo”, símbolo de Polifilo, pues “pan” significa todo o “poli” y la terminación “filo” coincide con el original, además conocidas son sus aficiones sobre temas esotéricos y las amistades con personajes que han tratado estos temas como Papus o Eliphas Levi, siendo él quien presentó a Julio Verne, entonces un joven, al editor Pierre Jules Hetzel.

Dumas fue notable como masón y libertario apoyando proyectos unificadores como el de Garibaldi en Italia, en cambio su amigo Hetzel se dejó notar como activista político, aunque ambos han colaborado estrechamente en los mismos proyectos.

Dumas y Hetzel son decisivos en la Sociedad de la Niebla, pues mientras Dumas buscaba y captaba nuevos valores literarios a través de los cuales se podría propagar la ideología de la Niebla, Hetzel les editaba sus obras, se las distribuía y promocionaba como nadie.

Uno de los personajes de Verne en su novela “La vuelta al mundo en 80 dias”, Philéas Fogg, esconde un nuevo Polifilo en su trama, pues etimológicamente puede descomponerse en “eas” que en griego significa todo y es el equivalente de Poli, y Fogg en inglés significa niebla. Pero hay más, ya que Philéas Fogg pertenece al selecto club llamado “Reform Club”, otra vez queda patente el deseo de reformar o transmutar, cuyas iniciales coinciden con las de la sociedad Rosa-Cruz además de dotarle de una de las características de la alquimia: la inmortalidad, pues lo describe como “un byron impasible que parece haber vivido miles de años sin envejecer”.

La Sociedad de la Niebla estableció una especie de complot para que se transformase el cristianismo mediante los rituales inspirados en los misterios de la sangre y que estaba financiado por la casa de los Habsburgo, pretendiendo secretamente realizar los ideales anárquicos de la Niebla mediante una profunda transformación social en todos los ámbitos: “desacreditar a todas las casas reales europeas para establecer una única dinastía reinante e institucionalizar la figura de un Gran Monarca en Europa, objetivo perseguido asimismo por otros grupos como el Priorato de Sión”.

Aquí tenemos el Gran Priorato de España, cuyo objetivo es cambiar el mundo a partir de la educación.

¿Qué hacían en estas reuniones? Poco se sabe de sus cónclaves, salvo que aprovechaban para hablar de política y literatura. Sus principales sesiones consistían en leer pasajes de El sueño de Polifilo, algo que parece absurdo a priori, salvo que existiera algún secreto que desconocemos

Toda sociedad secreta que se precie tiene que ser eso, secreta y lo más discreta posible. La Sociedad de la Niebla casi consigue esos dos objetivos.

Hasta hace muy pocos años, su existencia había quedado muy bien camuflada. Se trataba de una sociedad artística-literaria-mística-masó— nica, muy influida por las doctrinas rosacruces y en la que estaban «todos los que tenían que estar».

Haciendo un símil cinematográfico, era una especie de Club de los poetas muertos en la que se reunían novelistas, poetas, pintores, políticos y artistas en general para estudiar un libro raro:

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, también conocido como El sueño de Polifilo, una obra impresa por Aldo Manucio en Venecia, en el año 1499.

Sobre su posible autor, Francesco Colonna, y su contenido, todo son especulaciones. Está escrito en latín vulgar, con mezcla de griego, lombardo, y voces hebreas y caldeas. Y para complicarlo más, el autor utilizó palabras inventadas y un lenguaje arcaizante que ha sacado de quicio a sus críticos y traductores.

En el

mismo se describen los amores eróticos y alegóricos entre Polifilo y una

tal Polia. Se sabe tan poco de su profundo significado que desde el

siglo XVI se ha visto rodeado de un aura esotérica. De hecho, estamos

ante uno de los libros más curiosos y enigmáticos del Renacimiento, una

obra tan fascinante que ha cautivado a grandes intelectuales de todas

las épocas y, en concreto, a varios escritores franceses del siglo XIX.

Según las investigaciones de Michel Lamy —reflejadas en su obra Jules Verne, initíé et initiateur

(1984)—, Julio Verne pertenecía a esta sociedad secreta, llamada

Sociedad Angélica (también recibía el nombre de la Niebla, término que

designa para los francmasones el Principio Universal o caos originario

del que surge el Principio de la Verdad), que tenía como breviario o

texto básico el Hypnerotomachia Poliphili.

Lamy

comenta que esta sociedad fue fundada en el siglo XVI por el impresor

lionés Sébastien Gryphe, inspirándose en otra sociedad griega llamada Nephes

(que significa 'alma' en hebreo y 'niebla' en griego), que tenía como

símbolo al grifo, animal mitológico, y a la que pertenecían lumbreras

literarias como Rabelais o el pintor Poussin.

y a la que pertenecían lumbreras

literarias como Rabelais o el pintor Poussin.

y a la que pertenecían lumbreras

literarias como Rabelais o el pintor Poussin.

y a la que pertenecían lumbreras

literarias como Rabelais o el pintor Poussin.

Sobre Rabelais existen

suficientes evidencias que indican su pertenencia a una extraña Sociedad

Agla, que empleaba como emblema una «cifra de cuatro» como la que se

cree que utilizaban los antiguos cátaros para reconocerse entre sí.

En

cualquier caso, Lamy cree que «Agla» no es sino otra forma más de

definir a La Niebla.

Tras un largo letargo, la sociedad fue reactivada

en el siglo XIX y a ella se incorporaron, además de Julio Verne,

Alejandro Dumas, Gérard de Nerval, Gastón Lerroux, Maurice Leblanc,

Maurice Barres y George Sand, así como el pintor Delacroix, en cuyos

cuadros algunos críticos han querido ver rastros de El sueño de Polifilo.

Desde Rabelais, pasando por Cervantes hasta Julio Verne,

se ha creído que en esta obra se ocultan códigos secretos y mensajes

cifrados. La Sociedad de la Niebla tenía como objetivo analizar los

pasajes oscuros o fijarse en sus numerosos jeroglíficos para detectar

enigmas. Toda una sociedad secreta que gira en torno a un libro secreto

donde tan importante es el texto como los dibujos.

De hecho, algunos de

sus extraños grabados se han reproducido en pinturas o se han copiado en

esculturas, ex libris o fachadas de edificios. En España, por ejemplo,

se pueden ver varios esculpidos en las paredes del claustro de la

Universidad de Salamanca. Incluso los diseñadores de parques y jardines

románticos se han inspirado en sus diseños y a tal efecto se citan los

jardines de Versalles, en Francia, el de Bomarzo en Italia o el de

Aranjuez en España.

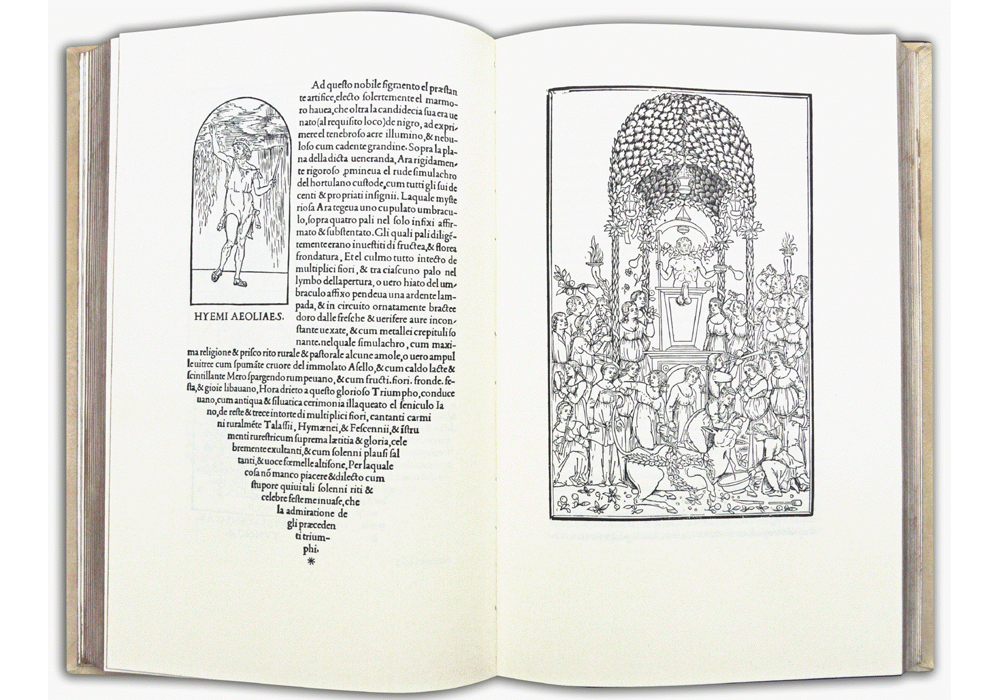

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (del griego hypnos, ‘sueño’, eros, ‘amor’ y mache, ‘lucha’), o el Sueño de Polífilo (discurso del) en castellano, es una obra de Francesco Colonna (1467). La edición original apareció en Venecia en 1499, en la imprenta de Aldo Manucio, con importantes xilografías, obra del Maestro del Sueño de Polífilo. Constituye una verdadera obra maestra del arte del libro, y obtuvo un gran éxito en el siglo XVI y en el siglo XVII, siendo traducido rápidamente a diversas lenguas.

Polyphilo: or The Dark Forest Revisited - An Erotic Epiphany of Architecture es una recreación moderna de la historia de Polyphilo por Alberto Pérez-Gómez, un eminente historiador de la arquitectura. El prólogo es una excelente introducción a la Hypnerotomachia.

Hablaré de un libro que, desde que se publicó en Venecia en 1499, tiene

un halo de misterio sobre su verdadero significado y su autor. Es la

historia bastante excéntrica y recargada, de los amores oníricos y un

tanto oscuros de un clérigo. Se trata del Hypnerotomachia Poliphili o El sueño de Polífilo cuyo autor, aún discutido, se cree que fue el monje dominico Francesco Colonna.

El “Sueño” es un poema alegórico de estirpe medieval con clara vocación enciclopédica, porque contiene conocimientos arqueológicos, arquitectónicos, litúrgicos, epigráficos, gemológicos y hasta culinarios. Pero, durantes siglos, son muchos los autores que han buceado en su verdadero significado y se han apuntado toda clases de teorías sin que aún ninguna sea la definitiva. Está claro, par un lector experto, que contiene muchas claves alquímicas, pero como digo, su verdadero significado, aún no ha sido revelado. No es extraño que, una misteriosa sociedad secreta a la que pertenecieron muchos escritores y artistas, tuvieran esta obra como libro de cabecera. Me refiero a la Sociedad de la Niebla.

El libro en realidad son dos escritos con distintas técnicas pero, según los expertos, proceden de la misma mano. Aunque parece que se unieron de una forma un tanto tosca. El primero nos cuenta el viaje onírico en primera persona de Polífilo, un viaje de carácter amoroso por regiones y construcciones alegóricas. Esto último podría explicar que, una de las primeras ediciones al castellano del libro, fuera hecha por el Colegio de Arquitectos de Valencia. En el segundo libro toma la palabra la amada Polia que se introduce en el mismo sueño.

Como dije, su autoría aún está en discusión. Poco se sabe de su autor y son varias las identidades que se barajan. Para unos Colonna era un fraile veneciano y para otros un noble romano. Aunque el original no apareció firmado, se llegó al nombre de Colonna de una forma harto curiosa. En una edición francesa del siglo XVI, el encargado de la traducción se dio cuenta que, uniendo las iniciales de los títulos de los capítulos, se podía leer: Poliam Frater Franciscus Columna Peramavit, y se relacionó este apellido con una famosa familia de la época. Ya en el siglo XX, hay autores que citan a un tal Felice Feliciano como autor del “Sueño” y aprecian en el acróstico solamente que: “Francesco amó a Polia”, pero no dice que escribiera el libro. Otras teorías hablan que el autor pudo ser León Battista Alberti, que fue poeta, arquitecto, lingüista, criptógrafo, arqueólogo… en fin, todas las materias que aparecen el en “Sueño”.

Lo que sí sabemos es quién lo financió, pero no con qué motivo. Fue el Duque Leonardo Grassi. No sabemos nada del autor de los grabados, y por lo que está obra adquirió fama. En cambio, el nombre del impresor sí que lo sabemos, y también se descubrió de una forma curiosa. Resulta que en una fe de erratas que sólo tenían algunas ediciones, se pudo leer “Aldo el Viejo, impresor”.

Sobre la lengua en que estaba escrito el original, también creó no pocos problemas a sus primeros lectores y traductores. En el texto se mezclaban el latín vulgar, el griego, el lombardo y hasta voces hebreas y caldeas. Pero para complicarlo más, su autor o autores, utilizaron palabras inventadas y un lenguaje pomposo y arcaizante que sacaba de quicio a sus críticos y traductores. Fue esta clara intención de enmascara el lenguaje, lo que le dio fama de libro esotérico, para iniciados. Es posible que la primera redacción se escribiera en italiano o latín, pero luego se encriptó con una mezcla de lenguas.

Son muchos autores que han citado o se han inspirado en el “Sueño”. Desde Rabelais hasta Cervantes. Alejandro Dumas escribió El capitán Pánfilo, de “pan”, que como “Poli”, significa “todo”, y “Filo”, que es “hijo”. Nerval se inspiró en el “Sueño” para su obra titulada Angelique. Rabelais utiliza algunos trucos del “Sueño” para esconder sus amores en Gargantúa. Rabelais era posiblemente Rosa-Cruz y Dumas, sin ninguna duda, perteneció a la Sociedad de la Niebla. Pero también tenemos rastros en las novelas de Julio Verne como El castillo de los Cárpatos o en el Viaje al centro de la Tierra, donde se habla de la fundación de una sociedad secreta formada por literatos. Hay autores que ven en el personaje de La vuelta al mundo en ochenta días, una referencia a lo que estamos hablando. En Phiélas Fogg estaría la clave. “Phiélas” puede descomponerse en “eas”, que en griego significa “todo”, que es equivalente a “Poli”. Lo del “Fogg” es más evidente, pues significa “niebla” en inglés.

Pero no hay que ir muy lejos para encontrar como este libro inspiró a pintores como Delacroix o Poussin. Basta con pasear por el Claustro de la Universidad de Salamanca, para ver en sus paredes grabados de este libro. Es más, hay zonas de los jardines de Aranjuez y de Versalles, que están sacados de las ilustraciones del “Sueño”.

Quizás, el “Sueño” sea el primer Manifiesto Hermético del Renacimiento. Un manual en clave donde se expresa una doctrina que se quería salvaguardar de las persecuciones. Una doctrina basada en la Vieja Religión, la de las corrientes neopaganas que practicaban en la Academia de los Príncipes y en las sociedades secretas de la época. Quizás ese amor a Polia sea el simbolismo de un amor a esos conocimientos heréticos y secretos. Pero todo, de momento, queda en un quizás, por lo menos por mí parte.

Nota: Los libros aquí referenciados no deben tomarse como una recomendación de lectura. Entre los libros “extraños” que tengo en mí biblioteca (en realidad el suelo y unas nórdicas estanterías) hay verdaderos peñazos que no recomendaría ni a mí peor enemigo. Algunos, ni siquiera después de los años, he podido entenderlos, como uno que les comentaré en unos días.

El “Sueño” es un poema alegórico de estirpe medieval con clara vocación enciclopédica, porque contiene conocimientos arqueológicos, arquitectónicos, litúrgicos, epigráficos, gemológicos y hasta culinarios. Pero, durantes siglos, son muchos los autores que han buceado en su verdadero significado y se han apuntado toda clases de teorías sin que aún ninguna sea la definitiva. Está claro, par un lector experto, que contiene muchas claves alquímicas, pero como digo, su verdadero significado, aún no ha sido revelado. No es extraño que, una misteriosa sociedad secreta a la que pertenecieron muchos escritores y artistas, tuvieran esta obra como libro de cabecera. Me refiero a la Sociedad de la Niebla.

El libro en realidad son dos escritos con distintas técnicas pero, según los expertos, proceden de la misma mano. Aunque parece que se unieron de una forma un tanto tosca. El primero nos cuenta el viaje onírico en primera persona de Polífilo, un viaje de carácter amoroso por regiones y construcciones alegóricas. Esto último podría explicar que, una de las primeras ediciones al castellano del libro, fuera hecha por el Colegio de Arquitectos de Valencia. En el segundo libro toma la palabra la amada Polia que se introduce en el mismo sueño.

Como dije, su autoría aún está en discusión. Poco se sabe de su autor y son varias las identidades que se barajan. Para unos Colonna era un fraile veneciano y para otros un noble romano. Aunque el original no apareció firmado, se llegó al nombre de Colonna de una forma harto curiosa. En una edición francesa del siglo XVI, el encargado de la traducción se dio cuenta que, uniendo las iniciales de los títulos de los capítulos, se podía leer: Poliam Frater Franciscus Columna Peramavit, y se relacionó este apellido con una famosa familia de la época. Ya en el siglo XX, hay autores que citan a un tal Felice Feliciano como autor del “Sueño” y aprecian en el acróstico solamente que: “Francesco amó a Polia”, pero no dice que escribiera el libro. Otras teorías hablan que el autor pudo ser León Battista Alberti, que fue poeta, arquitecto, lingüista, criptógrafo, arqueólogo… en fin, todas las materias que aparecen el en “Sueño”.

Lo que sí sabemos es quién lo financió, pero no con qué motivo. Fue el Duque Leonardo Grassi. No sabemos nada del autor de los grabados, y por lo que está obra adquirió fama. En cambio, el nombre del impresor sí que lo sabemos, y también se descubrió de una forma curiosa. Resulta que en una fe de erratas que sólo tenían algunas ediciones, se pudo leer “Aldo el Viejo, impresor”.

Sobre la lengua en que estaba escrito el original, también creó no pocos problemas a sus primeros lectores y traductores. En el texto se mezclaban el latín vulgar, el griego, el lombardo y hasta voces hebreas y caldeas. Pero para complicarlo más, su autor o autores, utilizaron palabras inventadas y un lenguaje pomposo y arcaizante que sacaba de quicio a sus críticos y traductores. Fue esta clara intención de enmascara el lenguaje, lo que le dio fama de libro esotérico, para iniciados. Es posible que la primera redacción se escribiera en italiano o latín, pero luego se encriptó con una mezcla de lenguas.

Son muchos autores que han citado o se han inspirado en el “Sueño”. Desde Rabelais hasta Cervantes. Alejandro Dumas escribió El capitán Pánfilo, de “pan”, que como “Poli”, significa “todo”, y “Filo”, que es “hijo”. Nerval se inspiró en el “Sueño” para su obra titulada Angelique. Rabelais utiliza algunos trucos del “Sueño” para esconder sus amores en Gargantúa. Rabelais era posiblemente Rosa-Cruz y Dumas, sin ninguna duda, perteneció a la Sociedad de la Niebla. Pero también tenemos rastros en las novelas de Julio Verne como El castillo de los Cárpatos o en el Viaje al centro de la Tierra, donde se habla de la fundación de una sociedad secreta formada por literatos. Hay autores que ven en el personaje de La vuelta al mundo en ochenta días, una referencia a lo que estamos hablando. En Phiélas Fogg estaría la clave. “Phiélas” puede descomponerse en “eas”, que en griego significa “todo”, que es equivalente a “Poli”. Lo del “Fogg” es más evidente, pues significa “niebla” en inglés.

Pero no hay que ir muy lejos para encontrar como este libro inspiró a pintores como Delacroix o Poussin. Basta con pasear por el Claustro de la Universidad de Salamanca, para ver en sus paredes grabados de este libro. Es más, hay zonas de los jardines de Aranjuez y de Versalles, que están sacados de las ilustraciones del “Sueño”.

Quizás, el “Sueño” sea el primer Manifiesto Hermético del Renacimiento. Un manual en clave donde se expresa una doctrina que se quería salvaguardar de las persecuciones. Una doctrina basada en la Vieja Religión, la de las corrientes neopaganas que practicaban en la Academia de los Príncipes y en las sociedades secretas de la época. Quizás ese amor a Polia sea el simbolismo de un amor a esos conocimientos heréticos y secretos. Pero todo, de momento, queda en un quizás, por lo menos por mí parte.

Nota: Los libros aquí referenciados no deben tomarse como una recomendación de lectura. Entre los libros “extraños” que tengo en mí biblioteca (en realidad el suelo y unas nórdicas estanterías) hay verdaderos peñazos que no recomendaría ni a mí peor enemigo. Algunos, ni siquiera después de los años, he podido entenderlos, como uno que les comentaré en unos días.

Sueño de Polífilo

Polífilo se arrodilla ante la Reina Eleuterylida.

Índice

Contenido

Se trata de «uno de los libros más curiosos y enigmáticos salidos de unas prensas», «oculta una rara hermosura y un apasionado anhelo de perfección, sabiduría y belleza absolutas, bajo el signo del Amor», «desde el mismo siglo XVI se ha visto rodeado de un aura de esoterismo enfermizo», «está, todavía hoy, envuelto en misterios». «En realidad, es un injerto de poema alegórico de estirpe medieval y enciclopedia humanística de vocación totalizadora, ya que contiene una ingente amalgama de conocimientos arqueológicos, epigráficos, arquitectónicos, litúrgicos, gemológicos y hasta culinarios».1Repercusión literaria

Además de aparecer citado en obras literarias (por ejemplo, en el siglo XVI en Gargantúa y Pantagruel, de François Rabelais, y en el XX en El Club Dumas, de Arturo Pérez-Reverte), sus elementos crípticos e iconográficos han sido objeto central de la exitosa novela de misterio de Ian Caldwell y Dustin Thomason The Rule of Four (El enigma del cuatro) ambientada en la Universidad de Princeton.Polyphilo: or The Dark Forest Revisited - An Erotic Epiphany of Architecture es una recreación moderna de la historia de Polyphilo por Alberto Pérez-Gómez, un eminente historiador de la arquitectura. El prólogo es una excelente introducción a la Hypnerotomachia.

Julio Verne dijo de sí mismo:

«Me siento el más desconocido de los hombres». Y es que todo en su vida

fue un verdadero misterio...

El primero captaba jóvenes valores literarios y había

escrito su novela, El capitán Pánfilo (1839),

como un guiño al grupo al que pertenecía, donde su protagonista va

manteniendo conversaciones con la elite de París. Recordemos que Pan, al

igual que el término Poli, significa 'todo' y Filo, 'hijo'. Hetzel, por

su parte, publicaba los libros de sus miembros divulgando

soterradamente sus ideas, promocionándolas a través de su Magazine d'Education et Récréation, dirigido por un notable masón llamado Jean Macé.

Verne, amigo de criptogramas, escribe en 1871 La vuelta al mundo en 80 días,

cuyo protagonista es Phileas Fogg, extraño nombre para un caballero

inglés que adquiere su auténtico significado cuando sabemos su

pertenencia a este grupo secreto:

Fogg es 'niebla' en inglés y Phileas

es el equivalente etimológico de Poliphilo (además Phileas puede

descomponerse en «eas» que en griego es 'todo' y equivale a Poli).

Otros

dicen que Phileas viene del latín filius

(hijo), lo que daría 'hijo de la niebla'. Los partidarios de esta

teoría, como Michel Lamy, tienden a vincular la creación del nombre con

las iniciales del Reform Club al cual pertenecía el inmutable y

flemático inglés. Ve en RC (las iniciales del nombre del club) una

alusión a la palabra Rosacruz, grupo ocultista cuya filosofía imitaba la

Sociedad de la Niebla.

En 1903, en una de las entrevistas que le

hiciese Robert Sherard, el autor francés, al hablar de este particular,

Verne expresó: «Le concedo cierta importancia a los nombres (...) Cuando

encontré el apellido Fogg me sentí complacido y orgulloso. Y era muy

popular. Fue considerado un hallazgo real. Pero fue especialmente el

nombre, Phileas, el que le dio tal valor a la creación. Sí, los nombres

tienen gran importancia. Siga como ejemplo los padrinazgos de Balzac».

Hubo otros miembros que destacaron por su labor

literaria y por divulgar sutilmente la existencia de la Sociedad de la

Niebla. Gérard de Nerval se inspiró en los mensajes cifrados de El sueño para componer algunos de sus relatos, como el titulado «Angelique», que forma parte de su obra Las hijas del fuego

(1854). George Sand, seudónimo que encubrió a la controvertida Aurore

Dupin, se dejará influenciar por la Sociedad Angélica utilizando, para

algunos de sus personajes fundamentales, nombres como Ange en su novela Spiridion y Angele en Consuelo.

Maurice Barrés, otro de los escritores de la

Niebla, además de político y amigo del místico Stanislas de Guaita, es

el autor de la novela La colina inspirada

(1913). Hay quien ha creído ver una referencia a Rennes-le-Cháteau, al

ser una obra en la que se insinúa la existencia de un gran complot para

transformar el cristianismo gracias al apoyo financiero de la casa real

de los Habsburgo, con el secreto propósito de instaurar la figura de un

gran monarca en Europa.

La Niebla estaba relacionada con otra sociedad

secreta de la época, la Golden Dawn, fundada en Inglaterra en 1887 y que

contaba con una logia en París. Entre sus miembros estaban el premio

Nobel William B. Yeats y Bram Stoker, cuyo Drácula muestra las ideas e influencias de esta sociedad.

En España existe una edición traducida y comentada de Hypnerotomachia Poliphili,

por la historiadora Pilar Pedraza, donde se intenta esclarecer su

importancia. En la introducción explica: «En realidad, es un poema

alegórico... que contiene una ingente amalgama de conocimientos

arqueológicos, epigráficos, arquitectónicos, litúrgicos, gemológicos y

hasta culinarios». No es de extrañar que encandilara a expertos e

investigadores de todos los tiempos, incluidos los intelectuales

franceses decimonónicos. Y su influjo continúa.

En nuestros días el Hypnerotomachia Poliphili se ha convertido en el argumento de un best setter.

Me refiero a El enigma del cuatro

(2004), de Ian Caldwell y Dustin Thomason, en el que sus protagonistas,

Paul Harris y Tom Sullivan, a punto de graduarse en la Universidad de

Princeton, intentan resolver un crimen sabiendo que en las ilustraciones

de esa obra se encuentran mensajes y claves ocultas que hay que

descifrar, algo que les llega a obsesionar. Los autores mezclan ficción

con datos reales, como el hecho curioso de que si se unen las iniciales

de los títulos de sus treinta y ocho capítulos, se puede leer:

«Poliam frater Eranciscus Columna peramavit», es decir, el nombre de su autor, Francesco Colonna, al parecer un fraile dominico veneciano.

Hoy sigue siendo un enigma tanto El sueño de Polifilo

como La Niebla, cuyos miembros lo tenían como libro de cabecera. No se

puede entender la una (la sociedad) sin la otra (la obra). Ya han pasado

más de quinientos años y seguimos casi como al principio. Quizá una de

las claves nos la dé una frase que aparece en uno de sus jeroglíficos:

«Apresúrate siempre despacio».

Haremos caso a esta máxima para que la sociedad que inspiró no se pierda en la «neblina» del tiempo...

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

by Philip Coppens

from PhilipCoppens Website

from PhilipCoppens Website

There was a “movement” named AGLA,

about which we know very little. As a secret society, it maintained

its nature very well. On first appearance, it seems they were an

underground movement that was not very active. However, this is a

dubious statement to make: as they were little known, bluntly

suggesting they were not very active is dangerous, owing to the fact

that we do not know anything about them, which means we know nothing

about their activities or frequency thereof either.

Robert Ambelain defines AGLA as an autonomous society and firmly closed. He suggests that rather than a subgroup, they were in fact the group behind a more visible organization, like for example, the organization led by another priest, Nicholas Montfaucon de Villars, author of “Count de Gabelis”, subtitled “The Extravagant Mysteries of the Cabalists, expounded in Five pleasant Discourses on the Secret Societies.”

The book which appeared in 1670, was a

treatise on the occult and elemental sex magic, assuring its ban in

France, even though it sold out several editions in the first few

months. Nevertheless, it had no known author, until Montfaucon’s

name was advanced. He was a well-known figure, a “Libertin”, an

intellectual whose ideas were deemed dangerous both for the church

and the king. In March 1673, De Villars was murdered by a rifle

bullet, near Lyons. His murder was never solved, but René Nelli

believes that Montfaucon de Villars had been assassinated, possibly

because in his book, he had revealed “too much”.

Villars wrote on

the topic of,

“the great name of AGLA, which operates all these wonders, at the same time as it is called upon by the ignoramuses and the sinners, and who would do many more miracles in a Kabbalistic fashion”.

What could this secret be that had to be

protected at all cost, even with the life of this priest? This

question remained unanswered, but raises another, almost identical

one: what could be the secret that had to be protected at all cost,

even with the life of the priest Antonin Gélis? No answer has ever

been provided for his murder either.

That murder occurred on the

evening of 31st October, 1897, in his presbytery. Newspaper accounts

relate how Gélis was found lying in a pool of blood, his arms placed

on his belly, but his legs in an awkward position, with one leg

firmly underneath the body. He had suffered 14 blows to the head,

fracturing his skull and even making the brain visible.

There were further minor injuries on the

rest of his body. Gélis had locked up the night before and it was

known he never let anyone in at night, unless he knew the person

visiting. With no signs of a break-in, it is clear that Gélis let

his murderer in – and was thus familiar with him. The murderer

killed the priest, but did not steal anything of value.

Although

cabinets had been gone through and some documents had been stolen,

nothing of value, including 500 Francs, had been taken. Newspaper

reports spoke of a “masked intruder” who had also broken into the

presbytery many years before and had got away with certain papers.

He was never found and now history was repeating itself and no-one

was ever charged with the murder.

One organization known as AGLA was not esoteric at all. That AGLA was, from its inception, only intended to attract invited members from the publishing industry: booksellers, printers, etc. The presence of a Rabelais, Nicholas Flamel, Sebastien Greif, Montfaucon de Villars would therefore not seem odd – neither would the booksellers of Lyons, who bought Saunière’s books. According to Robert Ambelain, AGLA also attracted the makers of the first sets of Tarot cards.

One organization known as AGLA was not esoteric at all. That AGLA was, from its inception, only intended to attract invited members from the publishing industry: booksellers, printers, etc. The presence of a Rabelais, Nicholas Flamel, Sebastien Greif, Montfaucon de Villars would therefore not seem odd – neither would the booksellers of Lyons, who bought Saunière’s books. According to Robert Ambelain, AGLA also attracted the makers of the first sets of Tarot cards.

There is AGLA, but there is also A.G.L.A. – written with all capital letters punctuated by a point. In this interpretation, “AGLA” would not be one word, but the abbreviation of four words. It is clear that this approach would be a clever “trick” – a smokescreen. For all intents and purposes, any observer would read AGLA or A.G.L.A. as an incorrect rendering of Agla – a society which had no esoteric connections whatsoever. Even if someone felt that A.G.L.A. could not be an error, but meant something else, there was no way for that person to know what each letter stood for – unless he had powerful computers at his disposal, or, more likely, came across someone who “knew”.

So what might A.G.L.A. stand for? One proposed reading is Attâh, Gibbor, Leholâm, Adonâi:

“Thou art strong for ever, O Lord”.

Actually, many people in Germany thought it stood for

“Almachtiger Gott Losch Aus!”

It is said to contain all the letters of

the Kaballah. Tradition has it that the Divine Power resides

within this simple set of four letters, containing at the same time

absolute knowledge, the science of Solomon and the Light of Abraham.

In other readings, it is the Secret or Hidden Name of God, so

cherished by the Kaballists, but also other esoteric traditions,

including the Freemasons. The question arises, therefore, as to

whether Saunière’s remotely guided steps were to direct him into

that direction?

The A.A. is a genuine organization – the very organization that was identified as the one to which Henri Boudet, the priest of Rennes-les-Bains, and Felix-Arsène Billard, the bishop of Carcassonne, belonged. However, trying to find information on the A.A. is next to impossible. We note that a document was found, which listed Boudet and two bishops of Carcassonne as members of this organization. This information was given to us by Gérard Moraux de Waldan.

The A.A. is a genuine organization – the very organization that was identified as the one to which Henri Boudet, the priest of Rennes-les-Bains, and Felix-Arsène Billard, the bishop of Carcassonne, belonged. However, trying to find information on the A.A. is next to impossible. We note that a document was found, which listed Boudet and two bishops of Carcassonne as members of this organization. This information was given to us by Gérard Moraux de Waldan.

It seems that several movements, at least four to our knowledge, claimed to be a part of this organization. However, although it was certainly present in more than 39 areas of France, only the Toulouse area seems to have had retained documents on the subject.

The general presentation of these little known groups shows a structure established on secrecy, accompanied by an undeniable spiritual improvement. At the time of the French Revolution, these secret societies opposed a clergy managed by a civil Constitution. One also finds their virulent action against the Napoleonic Regime during the plundering of the Vatican archives, the general confusion in Rome and the arrest of the pope.

According to Jean-Claude Meyer, in the Ecclesiastical Bulletin of Literature,

“The study of the AA of Toulouse, founded into the 17th century, forms part of the understanding of the more general movement of spiritual and apostolic reform of the clergy of France at that time. Beyond rules which appear out of date today, the history of this AA reveals the spirit of a sacerdotal fraternity lived by the fellow-members: thus is explained its exceptional longevity, one which will see the positive effects during the decade of the Revolution.”

There is also the work of Count

Bégouin who, in 1913, presented one of rare works on the subject

in the form of a work entitled:

EMULE DE LA COMPAGNIE DU SAINT-SACREMENT

L’AA DE TOULOUSE

AUX XVIIe et XVIIIe SIECLES

D’APRES DES DOCUMENTS INEDITS

EMULATING THE COMPANY OF THE SACRED SACRAMENT

THE AA OF TOULOUSE

FROM THE XXVII and XVIII CENTURY

ACCORDING TO UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPTS

On the bottom of the title page is the

address of the “editors”, set in two columns:

• on the left: “PARIS, Auguste Picard, rue Bonaparte 81”

• on the right-hand side: “TOULOUSE, Edouard Privat, rue des Arts, 14”.

At the bottom of the last page of text

(page 131), is the identity of the printer:

“Toulouse, Imp. Douladoure - Privat, rue St Rome, 30–678.”

Count Bégouin himself admits that

there are difficulties when he tries to base his argument on

previously unpublished documents, which are, of course, essential

for his work. These documents were extremely difficult to find,

although apparently some were said to exist in the region of Lyons

and Vienna, at the beginning of this century.

The starting point of Bégouin’s quest is the Parliamentary Decree of 13th December, 1660, marking the dissolution of the “Compagnie de St-Sacrement”. It also stated that it was now forbidden “to all people to make any assemblies, neither brotherhoods, congregations or communities” anywhere in France “without the express permission of the King”.

During the 17th century, the Compagnie de St Sacrement was a genuine movement which seems to have gone against the French King. It actually involved his mother, Anne of Austria, who seems to have plotted on the side of the conspirators, a group of people including Nicolas Pavillon, Vincent de Paul and, it seems, the Fouquet family. The statutes of the Compagnie stated that its sole goal was the “maintenance of the secret”. But the French king came down hard on the organization, and on any future attempt to reorganize it.

However, it seems that the AA’s original

role was to perpetuate the Compagnie, to maintain “the secret” – and

to make sure that this time, the powers that were, could not stop

them.

Curiously, one of the first documents to use the term A and AA, was published by Mr. Lieutaud, a librarian in Marseilles. It was in the reproduction of a report of 1775, on the AA of that city, written by its president, with the complete order of what was known as a “Société”. The title does not match up with the contents. It is curious that in a total of 16 pages, there is no reference to details of printing or the publisher. It is known as “A and AA, Preamble of a Future Encyclopaedia of Provence”.

It is difficult to understand the

relationship between the AA and an encyclopaedia of Provence,

however glorious its scenery is perceived to be. The same can be

said of another booklet, again without any references, entitled

“French history by a Carthusian monk”. Two further works on the same

topics would follow.

At this stage, two points demand our attention. First is the question as to how a librarian can publish books which lack all references; it is the very opposite of what his job description entails. Furthermore, as Bégouin himself stated, the titles are “odd and disconcerting”. Any normal search in a library would fail to come up with these booklets, except for someone who knew what he was looking for.

But even stranger collections would be published:

“A secret society of ecclesiastics in the seventeenth and eighteenth century - AA Cléricale - its history, its statutes, its mysteries”, with the epigraph: ‘Secretum prodere noli.’ To Mysteriopolis, with Jean de l’Arcanne, librarian of the Company, rue des trois cavernes, at Sigalion, in the back of the shop. MDCCCXCIII - with permission.”

On the back of the page, it reads:

“100 copies printed – none will be sold.”

The reference is so enigmatic that you

might suspect you had become a character in a detective novel! The “with

permission” reference is just one in a long series of incredible

details. Is it a hoax? A joke? Have these documents been falsified,

as has been the case in some instances in the mystery of Rennes-le-Château?

However, the booklet does exist and the reader will find that there

is an accompanying document at the end of the collection.

Our librarian Lieutaud never betrayed his sources, except to state:

“By ways that were both multiple and unexpected, the original parts that were used to compose this work fell into my hands. We are not authorized to say it, and thanks to God, though we never belonged to any AA, we know to maintain its secrecy.”

There is little else, except some

throwaway sentences:

“Knowing how jealously the last owners took care of these invaluable papers, keeping them contained and hidden, allows me suppose that, as for the Company of the Blessed Sacrament, we are far from knowing all the places where these files lie.”

On page 20, it explains that in

Toulouse, it had access to the files of the AA, which had more than

1,300 names of ecclesiastics from the Toulouse region who were

members.

This was not the only book of its kind. There was another such document printed in Lyons, at Baptiste de Ville, rue Mercière, in 1689. The book is extremely rare and unknown to bibliographers, just like yet another book, dated to 1654, which is intended “for a restricted number of initiates, those that belonged to the small group of elected officials comprising the AA”.

The reason for the choice of AA or A.A. as the title is never explained in the documents. It is argued that it comes from the expression “Associatio Alicorum”.

Others say it comes from taking

the two A’s from AssociAtion, and to present them in a

similar way to those that appear in certain alchemical writings such

as AAA, for the term “AmAlgAmer”, i.e. removing the

consonants to keep only the vowels.

If that were the case, such

coding is contrary to Egyptian or Kabbalistic writings, where

normally, the vowels are removed and the consonants kept, e.g. YHWH rather than

Yahweh – which

would be AE if the “vowel-retention cipher” had been used.

Bégouin himself believed that the AA should for “Amis” and “Assemblies”, Assembled Friends, thus summarizing the spirit of this company. Another assumption advanced by Lietaud is that AA stood for “Association Angelica” – the organization which, according to some, was related to “AGLA”.

One of the few letters sent by the AA does have the heading: J. M. J. A. C., which are the initials of: Jesus, Maria, Joseph, Angeli Custodes, i.e. Custodian Angels. This is an intriguing analysis. It seems to identify the AA somehow as being “Guardian Angels” of a “secret” that was at the heart of the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement, and its successor, the AA. Perhaps the AA is the Association of Angels?

The rule of the “secret” was absolute and without exemption. Admittedly, for certain researchers within this framework, the “secret” was simply that of the “good deeds performed under religious initiative”. But what is secret about “doing good”? If “good things” had to be kept secret, there are normally very good reasons for it – and the “good deeds” would not be of the everyday variety that you might do on weekends or weekday mornings in the church, those normally practiced by elderly men and women, who are “doing good” for the community.

Instead, the AA says:

“It is thus essential to maintain our secrecy. Reveal it to no-one, neither to the most intimate friends, nor to the dearest parents, not even to the most trustworthy confessor. Why would one speak with the confessor about it? In a project of this nature, that the only natural lights come from the Father of Light, a similar confidence was never necessary; it would always be imprudent and often contrary to the existence or the propagation of our AA.

Outside of the assemblies, the fellow-members will behave together as though no secret bond linked them. No sign, no word to make anyone suspect. In their letters, if they happen to mention the AA, it should only be in the shortest and most general terms possible. The AA will never be named, either in the letters, or in ordinary conversations. Those who have some papers relating to our Association on their premises, will preserve them with care and under key.”

Surely this is not “just” so that no-one

would know when the next cake stall is on – or what profit margin

there was on the second hand books sale? These rules are similar to

those of other secret societies, or societies, which require

initiation. It could be that of a Masonic lodge, as they could still

be found at the beginning of the 20th century.

But

whereas the secrecy of a Masonic lodge these days is a matter of

form, it seems clear that the AA is serious. The secrecy

instilled in their members is more along the lines of an

intelligence agency rather than a brotherhood of mutually interested

individuals.

But the question is whether the AA is a secret society, or a

discreet society. In the documents of the AA, the rules

relating to the secret start from page 71 onwards.

There is mention of a password, how to

envisage the self-destruction of the cell, to destroy all traces of

its existence, to pass from action to silence if there is the

slightest doubt. You can wonder whether terrorist organizations

practice such a level of secrecy. This type of moral convention is

of such an inconceivable rigor that the only framework in which this

document could come about is that of a fanatical sect… or of a

movement that was elected to safeguard a frightening secret.

It is difficult to believe that within the Church, there would be a company, made up of monks, that could impose such injunctions to protect themselves if their only goal was prayers, benevolence or charity. After all, “doing good” has always been out in the open; “doing bad” is normally done in secret.

There is another intriguing aspect to the AA. Under certain conditions, it allowed the admission of women from exclusively female congregations. Furthermore, laymen could, under very strict conditions, be accepted too. According to the type of members, they were distributed over several “congregations”.

For the Seminarists,

the AA rule envisaged a type of ante-room, called “Small

Company”. In this, the future priests were allowed to meet, without

ever knowing the “active members” of the brotherhood. As in all

other brotherhoods, there were several levels, or grades, in the

hierarchy. No doubt, the lower echelons had no idea what the higher

ranks were up to – as is the case in any hierarchical organization,

whether a business organization or a secret society.

Even so, at this stage it is still possible to consider that we are talking about a congregation, though of a very exceptional severity, reserved for a kind of religious elite… yet without being able to accept or acknowledge that it could be something else – something more obscure – secret.

Yet, that this is the case, is argued by the document itself:

“At the same time, behind this congregation or visible company, there was another occult one. It was the true AA, whose existence was a mystery and the name of the members an even greater mystery still. There were several political characters among them. The meetings were secret and certain members, in particular Prince de Polignac, only went to them in disguise. For on being allowed into this association, it was necessary to swear to absolute secrecy, to promise a blind obedience with passwords which no-one else knew.”

Prince Jules de Polignac (1780 -

March 29, 1847) was a French statesman, who played a conspicuous

part in the clerical and ultra-royalist reaction after the

Revolution.

If he attended such meetings, then it is clear that they

were important – and controversial. If we place Saunière in the same

environment, then we find a solid reason why he felt he could never

divulge the origins of his income – not to his bishop, or to anyone

else. He had sworn himself to it – to protect “the secret”. Although

it might seem bizarre that a small village priest should become a

member of such a notorious organization, he was a priest – somehow

predisposed towards joining the AA – and a discovery in his

church might have propelled him to the forefront of their attention

– and their cash flow.

It is clear that if Boudet and Billard were members of this organization – and the evidence suggests they were – then they too would be part of this secret brotherhood. It would seem that de Beauséjour was not…

The AA is the best candidate for the framework in which Saunière and his closest allies operated; membership of the AA could explain the extreme level of secrecy that Saunière adhered to – at the same time being instructed on how to maintain that secrecy so that his “double life” would never be known…

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario