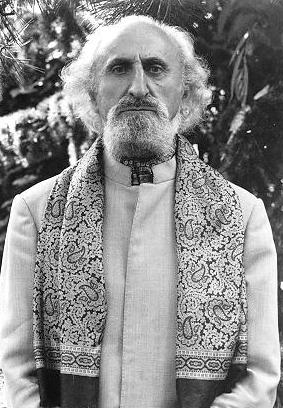

Frithjof Schuon (1907-1998) Metafísico, Poeta y Artista

Verdadera suma metafísica, obra maestra de equilibrio y de matices, la obra escrita de Frithjof Schuon es la expresión misma de la potencia de su genio didáctico. Por su objetividad y rigor, es una respuesta a los interrogantes del hombre actual, que se encuentra hoy desarmado ante las certidumbres dominantes de la ciencia y ante el nihilismo del ambiente. Schuon, sin embargo, no fue un metafísico libresco, como tantos otros, sino ante todo un hombre de oración inspirado, un verdadero sabio, y, por decirlo con la expresión que él utilizó respecto a Guénon, un "gnóstico nato", que tenderá a "encarnar su arquetipo" plenamente actualizando toda su riqueza interior.

Jean-Baptiste Aymard

Cita extraída del artículo Frithjof Schuon (1907-1998) Connaissance et Voie d'Intériorité. Approche biographique, 79 páginas, in Connaissance des Religions, Numéro Hors Série Frithjof Schuon, 1999, coédition Connaissance des Religions/Le Courrier du Livre

Copyright© 2004 Frithjof Schuon

FRITHJOF SCHUON (metafisico, poeta, pintor, artista ..

es considerado como uno de los máximos estudiosos y transmisores de las doctrinas tradicionales.

Su obra completa está siendo traducida y editada en español por Editorial Olañeta.

Biographía

Bibliographía

Pinturas

Poesías

Dossier H sobre F. Schuon

Volumen de poesías

Una metafisica de la naturaleza virgen

Sobre Arte y Naturaleza

Sobre la Naturaleza

El chamanismo de los indios pieles rojas

Fragmentos de una conversacion

con Frithjof Schuon

La mentalidad simbolista

Arte

Fundamentos de una Estetica integral

Criteriologia elemental de las apariciones celestiales

Apariciones Sensibles

La Virgen María

El sentido de lo sagrado

Prefacio, De la Unidad Transcendente de las ReligionesEsquema del Mensaje Cristico

Mahashakti

Perlas de SabiduríaSobre los Eastados Postumos

Escatologia universal

Sombras cósmicas y serenidad

La obra de Frithjof Schuon "tiene la autoridad intrínseca de una inteligencia contemplativa... una plenitud de luz que no tenemos derecho a esperar en el siglo XX, o quizá incluso en ningún otro siglo... Frithjof Schuon habla de la Gracia como alguien en quien ésta es operativa y, por decirlo así, en virtud de esta operación".

Bernard Kelly

"Esencialidad, universalidad y amplitud caracterizan a los escritos de Frithjof Schuon (...) Schuon posee el don de llegar al corazón mismo del tema tratado, de ir, más allá de las formas, al Centro aformal de éstas, ya sean religiosas, artísticas o ligadas a determinados aspectos o elementos de los órdenes humanos o cósmicos".

Seyyed Hossein Nasr.

BIBLIOGRAPHIA

De la unidad transcendente de las Religiones, 1948

El Ojo del Corazón, 1950

Perspectivas espirituales y hechos humanos, 1953

Senderos de Gnosis, 1957

Castas y Razas, 1957

Las estaciones de la Sabiduría, 1958

Imágenes del Espíritu, 1961

Comprender el Islam, 1961

Miradas sobre los mundos antiguos, 1965

Lógica y Transcendencia, 1970

Forma y substancia en las religiones, 1975

El esoterismo como principio y como vía, 1978

El Sufismo, velo y quintaesencia, 1980

Cristianismo-Islam, visiones de ecumenismo esotérico, 1981

De lo Divino a lo humano, 1981

Sobre las huellas de la Religión perenne, 1982

Acercamiento al fenómeno religioso, 1984

Resumen de metafísica integral, 1985

Tener un centro, 1988

Raíces de la condición humana, 1990

Las Perlas del peregrino, 1990

El juego de Máscaras, 1992

La transfiguración del hombre, 1995

Tesoros del Budismo, 1997

Bibliographía

Casas editoriales:

En España: José J. de Olañeta, Editor, Palma de Mallorca

Nouveau livre inspiré de l'oeuvre de F. Schuon : De Solo A Solo en el Nombre, Diario Espiritual

(some samples)

Copyright© 2001-2004 Frithjof Schuon

Copyright© 2001-2004 Frithjof Schuon

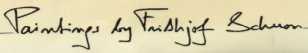

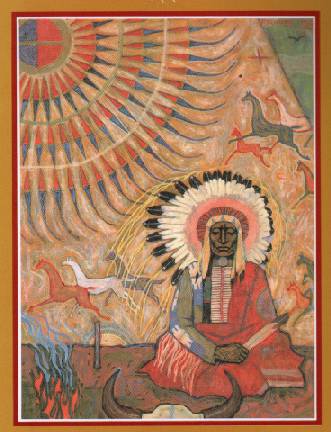

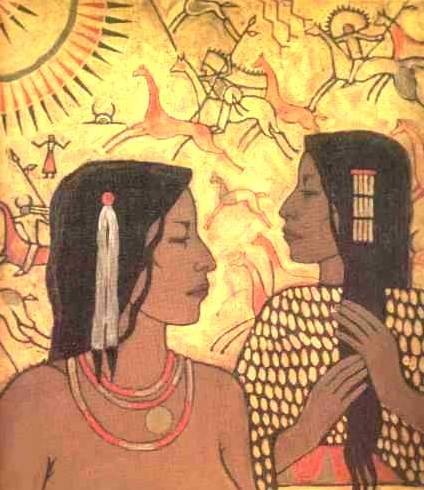

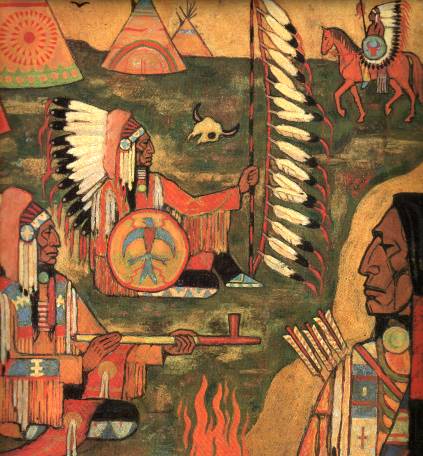

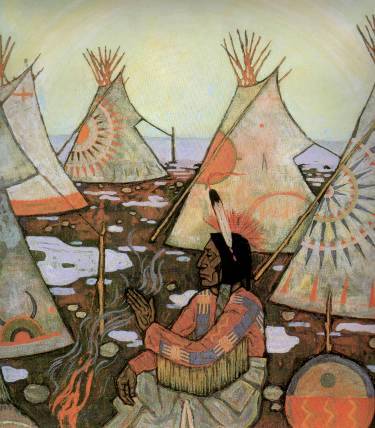

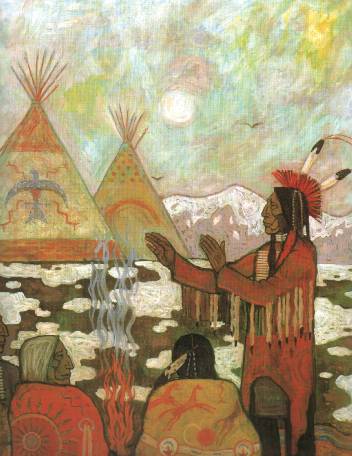

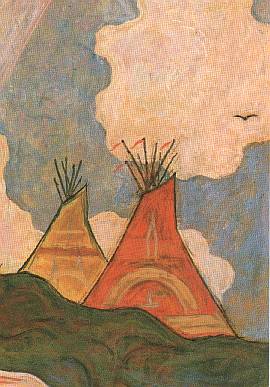

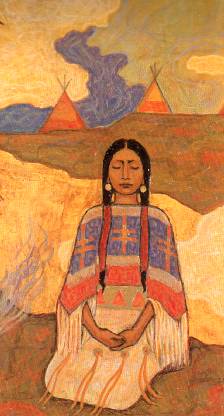

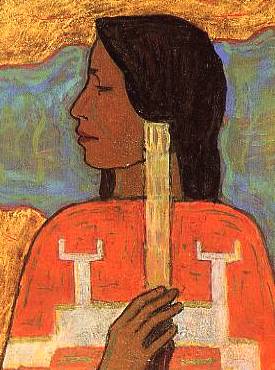

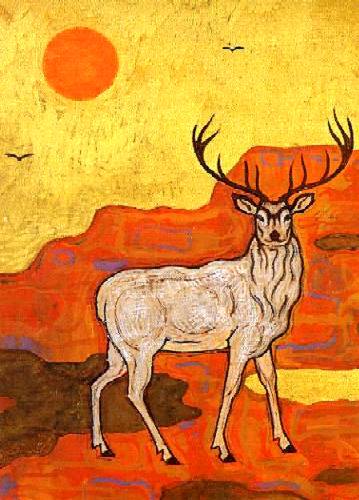

Frithjof Schuon was not only a metaphysician in the tradition of Shankara, Plato, Plotinus and Meister Eckhart, he was also a painter.

His paintings, sketches and drawings illustrate with depth and talent the aesthetic principles expressed in his books ("The Beautiful is the Splendor of the True" as he liked to remind it) and in his poetry. He wrote several chapters about art in various books.

His paintings, sketches and drawings illustrate with depth and talent the aesthetic principles expressed in his books ("The Beautiful is the Splendor of the True" as he liked to remind it) and in his poetry. He wrote several chapters about art in various books.

What is striking, in all these texts, is to see how much Schuon manifests a deep sense of forms, visual forms and colors for that matter. For him, the forms which surround us condition strongly, and insidiously when they are ugly, our soul. The modern world, the world of industrial societies, as opposed to traditional worlds, those which are mostly determined by one of the great religions, displays almost everywhere the cult of the ugly and of the offensive. Reacting against this quite "diabolical" tendency, Schuon redefines, with an amazing clarity, what the Beautiful is objectively (a definition which has nothing to do with the notions of neoclassical aesthetic canon) and leads us, throughout his books, to all the "beauties" that mankind produced throughout history, in order to extract their quintessence.

As for his paintings, they express the most intimate and inward aspects of his doctrine

(Ends, the visible and the Intelligible, meet). See, below and throughout this site, some examples of these paintings. For a hard copy of most of Frithjof Schuon's paintings, see the two books published by World Wisdom Books and Abodes:

(Ends, the visible and the Intelligible, meet). See, below and throughout this site, some examples of these paintings. For a hard copy of most of Frithjof Schuon's paintings, see the two books published by World Wisdom Books and Abodes:

- The Feathered Sun, Plains Indians in art and Philosophy, by Frithjof Schuon, with an introduction by Thomas Yellowtail, World Wisdom Books, USA

- Images of Primordial and Mystic Beauty, paintings by Frithjof Schuon and one of his students, with an introduction by one of his associates; Abodes, Bloomington, Indiana, USA, Amazon.com.

Paintings 2 -- Paintings 3 -- Paintings 4

Peintures 1 -- Peintures 2 -- Peintures 3 -- Peintures 4 -- Peintures 5

Peintures 1 -- Peintures 2 -- Peintures 3 -- Peintures 4 -- Peintures 5

Message of a Vestimentary Art

"The existence of princely and priestly garments proves

that clothing confers a personality upon man,

that it expresses or manifests a function

which may transcend or ennoble the individual."

(To Have a Center, p. 159)

that clothing confers a personality upon man,

that it expresses or manifests a function

which may transcend or ennoble the individual."

(To Have a Center, p. 159)

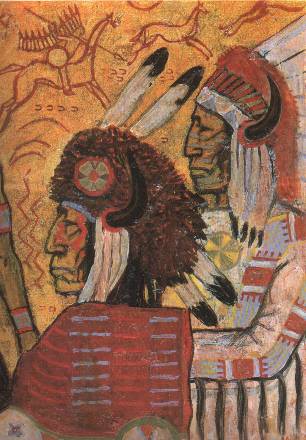

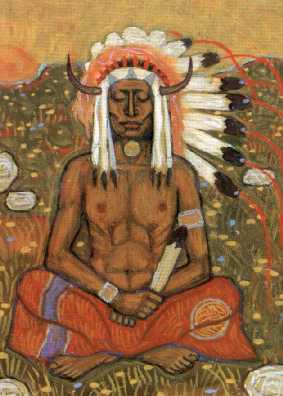

"One of the most powerful symbols of the sun is the majestic headdress

made of eagle feathers; he who wears it is identified with the solar orb,

and it is easy to understand that not everyone is qualified to wear it;

its splendor - unique of its kind among all traditional headdresses

in the world - suggests both royal and priestly dignity,

thus the radiance of the hero and the sage."

(To Have a Center, p.162)

made of eagle feathers; he who wears it is identified with the solar orb,

and it is easy to understand that not everyone is qualified to wear it;

its splendor - unique of its kind among all traditional headdresses

in the world - suggests both royal and priestly dignity,

thus the radiance of the hero and the sage."

(To Have a Center, p.162)

"According to the French authors Thévenin et Coze it is

"the most majestic headdress ever conceived by the human genius"

(Moeurs et Histoire des Indiens peaux-rouges).

Sometimes the feather bonnet is adorned with the horns of the buffalo,

which adds to it a pontifical symbol. The feathered spear - the solar ray -

prolongs the headdress in a dynamic and combative mode."

(To Have a Center, p.162, Note 3)

"the most majestic headdress ever conceived by the human genius"

(Moeurs et Histoire des Indiens peaux-rouges).

Sometimes the feather bonnet is adorned with the horns of the buffalo,

which adds to it a pontifical symbol. The feathered spear - the solar ray -

prolongs the headdress in a dynamic and combative mode."

(To Have a Center, p.162, Note 3)

Portraits of Indians

"Dignity is the ontological awareness

an individual has of his supra-individual reality."

(Spiritual perspectives and Human Facts, p. 210)

an individual has of his supra-individual reality."

(Spiritual perspectives and Human Facts, p. 210)

"Pride consists in taking ourselves for what we are not.

Self-respect is knowing what one is

and not allowing oneself to be humbled."

(Spiritual perspectives and Human Facts, p. 205)

Self-respect is knowing what one is

and not allowing oneself to be humbled."

(Spiritual perspectives and Human Facts, p. 205)

"Forms allow of a direct and 'plastic' assimilation

of the truths - or the realities - of the spirit."

(Spiritual perspectives and Human Facts, p. 28)

of the truths - or the realities - of the spirit."

(Spiritual perspectives and Human Facts, p. 28)

"Beauty mirrors happiness and truth. Without the element of 'happiness'

there remains only the bare form, geometrical, rhythmical or other;

and without the element of 'truth' there remains only

a wholly subjective enjoyment, or luxury if you will.

Beauty stands between abstract form and blind pleasure,

or rather combines the two so as to imbue veridical form with pleasure

and veridical pleasure with form."

(Spiritual perspectives and Human Facts, p. 29)

there remains only the bare form, geometrical, rhythmical or other;

and without the element of 'truth' there remains only

a wholly subjective enjoyment, or luxury if you will.

Beauty stands between abstract form and blind pleasure,

or rather combines the two so as to imbue veridical form with pleasure

and veridical pleasure with form."

(Spiritual perspectives and Human Facts, p. 29)

Copyright© 2001-2003 Frithjof Schuon

Copyright© 2001-2003 Frithjof Schuon

(All rights reserved)

(All rights reserved)

Copyright© 2001-2003 Frithjof Schuon

(All rights reserved)

(All rights reserved)

Copyright© 2001-2003 Frithjof Schuon

(All rights reserved)

(All rights reserved)

Copyright© 2001-2003 Frithjof Schuon

Copyright© 2001-2003 Frithjof Schuon

Copyright© 2001-2003 Frithjof Schuon

(All rights reserved)

(All rights reserved)

Copyright© 2001-2003 Frithjof Schuon

Copyright© 2001-2003 Frithjof Schuon

(All rights reserved)

(All rights reserved)

Copyright© 2001-2004 Frithjof Schuon

Copyright© 2001-2003 Frithjof Schuon

Copyright© 2001-2003 Frithjof Schuon

Copyright© 2001-2003Frithjof Schuon

(All rights reserved)

(All rights reserved)

Copyright© 2001-2003Frithjof Schuon

(All rights reserved)

(All rights reserved)

Copyright© 2001-2003Frithjof Schuon

(All rights reserved)

(All rights reserved)

Copyright© 2001-2004 Frithjof Schuon

(1907-1998)

Metafísico, Poeta y Artista

Verdadera suma metafísica, obra maestra de equilibrio y de matices, la obra escrita de Frithjof Schuon es la expresión misma de la potencia de su genio didáctico. Por su objetividad y rigor, es una respuesta a los interrogantes del hombre actual, que se encuentra hoy desarmado ante las certidumbres dominantes de la ciencia y ante el nihilismo del ambiente. Schuon, sin embargo, no fue un metafísico libresco, como tantos otros, sino ante todo un hombre de oración inspirado, un verdadero sabio, y, por decirlo con la expresión que él utilizó respecto a Guénon, un "gnóstico nato", que tenderá a "encarnar su arquetipo" plenamente actualizando toda su riqueza interior.

Jean-Baptiste Aymard

Cita extraída del artículo Frithjof Schuon (1907-1998) Connaissance et Voie d'Intériorité. Approche biographique, 79 páginas, in Connaissance des Religions, Numéro Hors Série Frithjof Schuon, 1999, coédition Connaissance des Religions/Le Courrier du Livre

Copyright© 2004 Frithjof Schuon

All rights reserved

English Français Português

FRITHJOF SCHUON

es considerado como uno de los máximos estudiosos y transmisores de las doctrinas tradicionales.

Su obra completa está siendo traducida y editada en español por Editorial Olañeta.

Biographía

Bibliographía

Pinturas

Poesías

Dossier H sobre F. Schuon

Volumen de poesías

Una metafisica de la naturaleza virgen

Sobre Arte y Naturaleza

Sobre la Naturaleza

El chamanismo de los indios pieles rojas

Fragmentos de una conversacion

con Frithjof Schuon

La mentalidad simbolista

Arte

Fundamentos de una Estetica integral

Criteriologia elemental de las apariciones celestiales

Apariciones Sensibles

La Virgen María

El sentido de lo sagrado

Prefacio, De la Unidad Transcendente de las ReligionesEsquema del Mensaje Cristico

Mahashakti

Perlas de SabiduríaSobre los Eastados Postumos

Escatologia universal

Sombras cósmicas y serenidad

La obra de Frithjof Schuon "tiene la autoridad intrínseca de una inteligencia contemplativa... una plenitud de luz que no tenemos derecho a esperar en el siglo XX, o quizá incluso en ningún otro siglo... Frithjof Schuon habla de la Gracia como alguien en quien ésta es operativa y, por decirlo así, en virtud de esta operación".

Bernard Kelly

"Esencialidad, universalidad y amplitud caracterizan a los escritos de Frithjof Schuon (...) Schuon posee el don de llegar al corazón mismo del tema tratado, de ir, más allá de las formas, al Centro aformal de éstas, ya sean religiosas, artísticas o ligadas a determinados aspectos o elementos de los órdenes humanos o cósmicos".

Seyyed Hossein Nasr.

BIBLIOGRAPHIA

De la unidad transcendente de las Religiones, 1948

El Ojo del Corazón, 1950

Perspectivas espirituales y hechos humanos, 1953

Senderos de Gnosis, 1957

Castas y Razas, 1957

Las estaciones de la Sabiduría, 1958

Imágenes del Espíritu, 1961

Comprender el Islam, 1961

Miradas sobre los mundos antiguos, 1965

Lógica y Transcendencia, 1970

Forma y substancia en las religiones, 1975

El esoterismo como principio y como vía, 1978

El Sufismo, velo y quintaesencia, 1980

Cristianismo-Islam, visiones de ecumenismo esotérico, 1981

De lo Divino a lo humano, 1981

Sobre las huellas de la Religión perenne, 1982

Acercamiento al fenómeno religioso, 1984

Resumen de metafísica integral, 1985

Tener un centro, 1988

Raíces de la condición humana, 1990

Las Perlas del peregrino, 1990

El juego de Máscaras, 1992

La transfiguración del hombre, 1995

Tesoros del Budismo, 1997

Bibliographía

Casas editoriales:

En España: José J. de Olañeta, Editor, Palma de Mallorca

Nouveau livre inspiré de l'oeuvre de F. Schuon : De Solo A Solo en el Nombre, Diario Espiritual

Frithjof Schuon (/ˈʃuːɑːn/; German: [ˈfʀiːtˌjoːf ˈʃuːˌɔn]; June 18, 1907 – May 5, 1998) was born to German parents in Basel, Switzerland. He is known as a philosopher, metaphysician and author of numerous books on religion and spirituality

Schuon

is recognized as an authority on philosophy, spirituality and religion, an exponent of the Religio Perennis, and one of the chief representatives of thePerennialist School. Though he was not officially affiliated with the academic world, his writings have been noticed in scholarly and philosophical journals, and by scholars of comparative religion andspirituality. Criticism of the relativism of the modern academic world is one of the main aspects of Schuon's teachings. In his teachings, Schuon expresses his faith in an absolute principle, God, who governs the universe and to whom our souls would return after death. For Schuon the great revelations are the link between this absolute principle—God—and mankind. He wrote the main bulk of his metaphysical teachings in French. In the later years of his life Schuon composed some volumes of poetry in his mother tongue, German. His articles in French were collected in about twenty titles in French which were later translated into English as well as many other languages. The main subjects of his prose as well as his poetic compositions are spirituality and various essential realms of man's life journey from his Creator back to Him.[1]

is recognized as an authority on philosophy, spirituality and religion, an exponent of the Religio Perennis, and one of the chief representatives of thePerennialist School. Though he was not officially affiliated with the academic world, his writings have been noticed in scholarly and philosophical journals, and by scholars of comparative religion andspirituality. Criticism of the relativism of the modern academic world is one of the main aspects of Schuon's teachings. In his teachings, Schuon expresses his faith in an absolute principle, God, who governs the universe and to whom our souls would return after death. For Schuon the great revelations are the link between this absolute principle—God—and mankind. He wrote the main bulk of his metaphysical teachings in French. In the later years of his life Schuon composed some volumes of poetry in his mother tongue, German. His articles in French were collected in about twenty titles in French which were later translated into English as well as many other languages. The main subjects of his prose as well as his poetic compositions are spirituality and various essential realms of man's life journey from his Creator back to Him.[1]Contents [hide]

1 Biography

2 Views

2.1 Transcendent unity of religions

2.2 Metaphysics

2.3 Religio perennis

2.4 Spiritual path

2.5 Quintessential esoterism

2.6 Criticism of modernity

3 See also

4 References

5 Bibliography

6 External links

[edit]Biography

Schuon was born in Basel, Switzerland, on June 18, 1907. His father was a native of southernGermany, while his mother came from an Alsatian family. Schuon's father was a concert violinist and the household was one in which not only music but literary and spiritual culture were present. Schuon lived in Basel and attended school there until the untimely death of his father, after which his mother returned with her two young sons to her family in nearby Mulhouse, France, where Schuon was obliged to become a French citizen. Having received his earliest training in German, he received his later education in French and thus mastered both languages early in life.[citation needed]

From his youth, Schuon's search for metaphysical truth led him to read the Upanishads and theBhagavad Gita. While still living in Mulhouse, he discovered the works of René Guénon, the French philosopher and Orientalist, which served to confirm his intellectual intuitions and which provided support for the metaphysical principles he had begun to discover.[citation needed]

Schuon journeyed to Paris after serving for a year and a half in the French army. There he worked as a textile designer and began to study Arabic in the local mosque school. Living in Paris also brought the opportunity to be exposed to various forms of traditional art to a much greater degree than before, especially the arts of Asia with which he had had a deep affinity since his youth. This period of growing intellectual and artistic familiarity with the traditional worlds was followed by Schuon's first visit toAlgeria in 1932. It was then that he met the celebrated Shaykh Ahmad al-Alawi and was initiated into his order.[2] On a second trip to North Africa, in 1935, he visited Algeria and Morocco; and during 1938 and 1939 he traveled to Egypt where he met Guénon, with whom he had been in correspondence for 27 years. In 1939, shortly after his arrival in Pie,India, World War II broke out, forcing him to return to Europe. After having served in the French army, and having been made a prisoner by the Germans, he sought asylum in Switzerland, which gave him Swiss nationality and was to be his home for forty years. In 1949 he married, his wife being a German Swiss with a French education who, besides having interests in religion and metaphysics, is also a gifted painter.[3]

Following World War II, Schuon accepted an invitation to travel to the American West, where he lived for several months among the Plains Indians, in whom he always had a deep interest. Having received his education in France, Schuon has written all his major works in French, which began to appear in English translation in 1953. Of his first book, The Transcendent Unity of Religions (London, Faber & Faber) T. S. Eliot wrote: "I have met with no more impressive work in the comparative study of Oriental and Occidental religion." [3]

While always continuing to write, Schuon and his wife traveled widely. In 1959 and again in 1963, they journeyed to the American West at the invitation of friends among the Sioux and Crow American Indians. In the company of their Native American friends, they visited various Plains tribes and had the opportunity to witness many aspects of their sacred traditions. In 1959, Schuon and his wife were solemnly adopted into the Sioux family of James Red Cloud. Years later they were similarly adopted by the Crow medicine man and Sun Dance chief, Thomas Yellowtail. Schuon's writings on the central rites of Native American religion and his paintings of their ways of life attest to his particular affinity with the spiritual universe of the Plains Indians. Other travels have included journeys to Andalusia, Morocco, and a visit in 1968 to the home of the Holy Virgin in Ephesus. In 1980, Schuon and his wife emigrated to the United States, where he continued to write until his death in 1998.[citation needed]

Through his many books and articles, Schuon became known as a spiritual teacher and leader of theTraditionalist School. During his years in Switzerland he regularly received visits from well-known religious scholars and thinkers of East.[citation needed]

[edit]Views

[edit]Transcendent unity of religions

The traditionalist or perennialist perspective began to be enunciated in the 1920s by the French philosopher René Guénon and, in the 1930s, by Schuon himself. The Harvard orientalist Ananda Coomaraswamy and the Swiss art historian Titus Burckhardt also became prominent advocates of this point of view. Fundamentally, this doctrine is the Sanatana Dharma – the "eternal religion" – of Hindu Neo-Vedantins. It was supposedly formulated in ancient Greece, in particular, by Plato and laterNeoplatonists, and in Christendom by Meister Eckhart (in the West) and Gregory Palamas (in the East). Every religion has, besides its literal meaning, an esoteric dimension, which is essential, primordial and universal. This intellectual universality is one of the hallmarks of Schuon's works, and it gives rise to insights into not only the various spiritual traditions, but also history, science and art.[citation needed]

The dominant theme or principle of Schuon's writings was foreshadowed in his early encounter with a Black marabout who had accompanied some members of his Senegalese village to Switzerland in order to demonstrate their culture. When the young Schuon talked with him, the venerable old man drew a circle with radii on the ground and explained: God is in the center; all paths lead to Him.[citation needed]

[edit]Metaphysics

For Schuon, the quintessence of pure metaphysics can be summarized by the following vedantic statement, although the Advaita Vedanta's perspective finds its equivalent in the teachings of Ibn Arabi, Meister Eckhart or Plotinus: Brahma satyam jagan mithya jivo brahmaiva na'parah (Brahman is real, the world is illusory, the self is not different from Brahman).[4]

The metaphysics exposited by Schuon is based on the doctrine of the non-dual Absolute (Beyond-Being) and the degrees of reality. The distinction between the Absolute and the relative corresponds for Schuon to the couple Atma/Maya. Maya is not only the cosmic illusion: from a higher standpoint, Maya is also the Infinite, the Divine Relativity or else the feminine aspect (mahashakti) of the Supreme Principle.

Said differently, being the Absolute, Beyond-Being is also the Sovereign Good (Agathon), that by its nature desires to communicate itself through the projection of Maya. The whole manifestation from the first Being (Ishvara) to matter (Prakriti), the lower degree of reality, is indeed the projection of the Supreme Principle (Brahman). The personal God, considered as the creative cause of the world, is only relatively Absolute, a first determination of Beyond-Being, at the summit of Maya. The Supreme Principle is not only Beyond-Being. It is also the Supreme Self (Atman) and in its innermost essence, the Intellect (buddhi) that is the ray of Consciousness shining down, the axial refraction of Atma within Maya.[5]

[edit]Religio perennis

Schuon, in more than twenty books written mainly in French, explains the metaphysical principles as well as the spiritual and moral aspects of human life. Schuon's religio perennis cannot be called a newreligion with its own dogma and practices. For Schuon, the religio perennis is the underlying religion, the religion of the heart or the religio cordis. Esoterists in every orthodox tradition have a more or less direct access to it, but it cannot be a question of practicing the religio perennis independently. Religious forms can be more or less transparent but religious diversity is not denied for its raison d'êtreis metaphysically explained. On the one hand, formal religions are upaya (providential saving stratagem), different manifestations of the core-essence of the religio perennis. On the other hand, religious forms correspond to as many archetypes in the divine Word itself. Religious forms are willed by God and each religion corresponds to a particular and homogenous cosmos, characterized by its own perspective of the Absolute.[6]

The Perennialist perspective itself can thus be characterized as essentially metaphysical, esoteric, primordial but also traditional. For Schuon, there is no spiritual path outside of a revealed religion, which provides spiritual seekers with a metaphysical doctrine and a spiritual method, but also with a spiritual environment of beauty and holiness.[7]

[edit]Spiritual path

According to Schuon the spiritual path is essentially based on the discernment between the "Real" and the "unreal" (Atma / Maya); concentration on the Real; and the practice of virtues. Human beings must know the "Truth". Knowing the Truth, they must then will the "Good" and concentrate on it. These two aspects correspond to the metaphysical doctrine and the spiritual method. Knowing the Truth and willing the Good, human beings must finally love "Beauty" in their own soul through virtue, but also in "Nature". In this respect Schuon has insisted on the importance for the authentic spiritual seeker to be aware of what he called the "metaphysical transparency of phenomena".[8]

Schuon wrote about different aspects of spiritual life both on the doctrinal and on the practical levels. He explained the forms of the spiritual practices as they have been manifested in various traditional universes. In particular, he wrote on the Invocation of the Divine Name (dhikr, Japa-Yoga, the Prayer of the Heart), considered by Hindus as the best and most providential means of realization at the end of the Kali Yuga. As has been noted by the Hindu saint Ramakrishna, the secret of the invocatory path is that God and his Name are one.[9]

[edit]Quintessential esoterism

Guénon had pointed out at the beginning of the twentieth century that every religion comprises two main aspects: "Esoterism" and "Exoterism". Schuon explained that the esoterism itself displays two aspects, one being an extension of exoterism and the other one independent of exoterism; for if it be true that the form "is" in a certain way the essence, the essence on the contrary is by no means totally expressed by a single form; the drop is water, but water is not the drop. This second aspect is called "quintessential esoterism" for it is not limited or expressed totally by one single form or theological school and, above all, by a particular religious form as such.[10]

[edit]Criticism of modernity

In his essay 'The Contradictions of Relativism' Schuon wrote that uncompromising relativism that underlies many modern philosophies had fallen into an intrinsic absurdity in declaring that there is no absolute truth and then attempting to put this forward as an absolute truth. Schuon notes that the essence of Relativism is found in the idea that we never escape from human subjectivity whilst its expounders seem to remain unaware of the fact that Relativism is therefore also deprived of any objectivity. Schuon further notes that the Freudian assertion that rationality is merely a hypocritical guise for a repressed animal drive results in the very assertion itself being devoid of worth as it is itself a rational judgment.[11]

[edit]See also

Traditionalist School

Titus Burckhardt

Martin Lings

Ananda Coomaraswamy

Jean-Louis Michon

Seyyed Hossein Nasr

Tage Lindbom

Kurt Almqvist

Ivan Aguéli

Michel Valsan

René Guénon

Huston Smith

William Stoddart

Whitall Perry

Michael Oren Fitzgerald

[edit]References

^ Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. pp. 1.ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

^ Frithjof Schuon, Songs Without Names, Volumes VII-XII, (World Wisdom, 2007) p. 226.

^ a b Frithjof Schuon's life and work.

^ Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. pp. 21. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

^ Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. pp. 37. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

^ Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. pp. 43. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

^ Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. pp. 59. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

^ Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. pp. 61. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

^ Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. pp. 73. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

^ Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. pp. 85. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

^ Logic and transcendence, Perennial Books, 1975.

[edit]Bibliography

Adastra and Stella Maris: Poems by Frithjof Schuon, World Wisdom, 2003

Art from the Sacred to the Profane: East and West, (A selection from his writings by Catherine Schuon), World Wisdom, Inc, 2007. ISBN 1933316357

Castes and Races, Perennial Books, 1959, 1982

Christianity/Islam, World Wisdom, 1985

New translation, World Wisdom, 2008

Echoes of Perennial Wisdom, World Wisdom, 1992

Esoterism as Principle and as Way, Perennial Books, 1981, 1990

The Essential Frithjof Schuon, World Wisdom, 2005

The Essential Writings of Frithjof Schuon (S.H. Nasr, Ed.), 1986, Element, 1991

The Eye of the Heart, World Wisdom, 1997

The Feathered Sun: Plain Indians in Art & Philosophy, World Wisdom, 1990

Form and Substance in the Religions, World Wisdom, 2002

From the Divine to the Human, World Wisdom, 1982

Gnosis: Divine Wisdom, 1959, 1978, Perennial Books 1990

New translation, World Wisdom, 2006

Images of Primordial & Mystic Beauty: Paintings by Frithjof Schuon, Abodes, 1992, World Wisdom

In the Face of the Absolute, World Wisdom, 1989, 1994

In the Tracks of Buddhism, 1968, 1989

New translation, Treasures of Buddhism, World Wisdom, 1993

Language of the Self, 1959

Revised edition, World Wisdom, 1999

Light on the Ancient Worlds, 1966, World Wisdom, 1984

New translation, World Wisdom, 2006

Logic and Transcendence, 1975, Perennial Books, 1984

The Play of Masks, World Wisdom, 1992

Prayer Fashions Man, World Wisdom, 2005

Road to the Heart, World Wisdom, 1995

Roots of the Human Condition, World Wisdom, 1991

New translation, World Wisdom, 2002

Songs for a Spiritual Traveler: Selected Poems, World Wisdom, 2002

Songs Without Names Vol. I-VI, World Wisdom, 2007

Songs Without Names VII-XII, World Wisdom, 2007

Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts, 1954, 1969

New translation, Perennial Books, 1987, New Translation, World Wisdom, 2007

Stations of Wisdom, 1961, 1980

Revised translation, World Wisdom, 1995

Sufism: Veil and Quintessence, World Wisdom, 1981

New translation, World Wisdom, 2007

Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism, World Wisdom, 1986, 2000

The Transcendent Unity of Religions, 1953

Revised Edition, 1975, 1984, The Theosophical Publishing House, 1993

The Transfiguration of Man, World Wisdom, 1995

To Have a Center, World Wisdom, 1990

Understanding Islam, 1963, 1965, 1972, 1976, 1979, 1981, 1986, 1989

Revised translation, World Wisdom, 1994, 1998

World Wheel Vol. I-III, World Wisdom, 2007

World Wheel Vol. IV-VII, World Wisdom, 2007

Schuon was a frequent contributor to the quarterly journal Studies in Comparative Religion, (along with Guénon, Coomarswamy, and many others) which dealt with religious symbolism and the Traditionalistperspective.

[edit]External links

Perennialist/Traditionalist School website

Schuon website

Fons Vitae books - Traditionalist School books

Frithjof Schuon Archive

World Wisdom - Perennial Philosophy

Dane Rudhyar filtered astrology through Jung’s archetypal and alchemical psychology, emerging with a vision of wholeness that’s never found a more effective expression.

From his final book, The Fullness of Human Experience:

What is to be meant by being a person? Why are human beings today determined to operate as autonomous individuals characteristically able to make responsible decisions? Another question inevitably follows: How does a person arrive at what he or she considers a valid basis for the decision? This basis evidently depends on the particular nature of the choice being made; yet, whether or not the person realizes it, any decision implies the acceptance of an approach to life and the meaning of existence which has metaphysical and/or religious roots.

Most religions or spiritual philosophies assume as an incontrovertible fact of inner experiences (particularly in states of intense meditation or ecstasy) that human persons are essentially spiritual entities (Souls or Monads) that, having emerged from “the One” (God or the Absolute), return to their source after a long and dangerous “pilgrimage” through a series of material states. Individuality, and therefore a state of at least relative separateness which allows for basic differences in beingness, are the essential factors in the human condition.

I would add that it is this “state of at least relative separateness” that is at the root of our 21st Century existential crisis — which is why a revival of Religio Perennis is essential to both the survival and wellbeing of the human species on planet Earth.

Why?

Because, without a metaphysical structure, we are left without a context through which this material reality may gain meaning. And without meaning, what’s the point in living?

It is this dirth of meaning that ends up pitting humans against humans, each projecting suffering onto the other, mindless of their essential unity.

On the other hand, with metaphysical meaning comes a recognition of our brotherhood and sisterhood — our collective status as children of The One — and it is this recognition that invites heaven on earth.

From Frithjof Schuon’s definition (.pdf) of Religio Perennis:

One of the keys to understanding our true nature and our ultimate destiny is the fact that the things of this world are never proportionate to the actual range of our intelligence. Our intelligence is made for the Absolute, or else it is nothing; among all the intelligences of this world the human spirit alone is capable of objectivity, and this implies—or proves—that the Absolute alone confers on our intelligence the power to accomplish to the full what it can accomplish and to be wholly what it is. If it were necessary or useful to prove the Absolute, the objective and trans-personal character of the human Intellect would be a sufficient testimony, for this Intellect is the indisputable sign of a purely spiritual first Cause, a Unity infinitely central but containing all things, an Essence at once immanent and transcendent. It has been said more than once that total Truth is inscribed in an eternal script in the very substance of our spirit; what the different Revelations do is to “crystallize” and “actualize”, in different degrees according to the case, a nucleus of certitudes that not only abides forever in the divine Omniscience, but also sleeps by refraction in the “naturally supernatural” kernel of the individual, as well as in that of each ethnic or historical collectivity or the human species as a whole.

(…) The essential function of human intelligence is discernment between the Real and the illusory or between the Permanent and the impermanent, and the essential function of the will is attachment to the Permanent or the Real. This discernment and this attachment are the quintessence of all spirituality; carried to their highest level or reduced to their purest substance, they constitute the underlying universality in every great spiritual patrimony of humanity, or what may be called the religio perennis; this is the religion to which the sages adhere, one which is always and necessarily founded upon formal elements of divine institution.

(…) A civilization is integral and healthy to the extent it is founded on the “invisible” or “underlying” religion, the religio perennis, that is, to the extent its expressions or forms are transparent to the Non-Formal and tend toward the Origin, thus conveying the recollection of a Lost Paradise, but also—and with all the more reason—the presentiment of a timeless Beatitude. For the Origin is at once within us and before us; time is but a spiral movement around a motionless Center.This last line says it all.

It is something toward which our species once aspired — our fallible, frail species — and with any luck, it’s an aspiration we’ll discover once again.

---

De la unidad transcendente de las religiones

Las consideraciones de este libro proceden de una doctrina que no es en absoluto filosófica, sino propiamente metafísica. Esta distinción puede parecer ilegítima a quienes tienen la costumbre de englobar la metafísica en la filosofía, pero, si se encuentra ya una tal asimilación en Aristóteles y en sus continuadores escolásticos, esto prueba precisamente que toda filosofía tiene limitaciones que, inclusive en los casos más favorables, toda filosofía tiene limitaciones que, inclusive en los casos más favorables, como los que acabamos de citar, excluyen una apreciación perfectamente adecuada a la metafísica. En realidad, ésta posee un carácter trascendente que la hace independiente de un pensamiento puramente humano, cualquiera que sea. Para definir bien la diferencia que existe entre uno y otro modo de pensamiento, diremos que la filosofía procede de la razón, facultad enteramente individual, mientras que la metafísica surge exclusivamente del Intelecto. Este último era definido de la siguiente manera, con pleno conocimiento de causa, por el maestro Eckhart: "En el alma hay algo que es increado e increable, y esto es el Intelecto". En el esoterismo musulmán se encuentra una definición análoga, aunque más concisa aún y más rica en valor simbólico: "El Sufí (es decir, el hombre identificado con el Intelecto) no es creado."

Si el conocimiento puramente intelectual sobrepasa por definición al individuo; si, por consiguiente, es de esencia supraindividual, universal o divina y procede de la Inteligencia pura, es decir, directa y no discursiva, hay que decir que este conocimiento no sólo va más lejos que el razonamiento, sino inclusive más lejos que la fe en el sentido ordinario de este término. Dicho de otro modo: el conocimiento intelectual sobrepasa igualmente el punto de vista específicamente religioso que, por su parte, es, sin embargo, incomparablemente superior al punto de vista filosófico, o, más precisamente, racionalista, puesto que, como el conocimiento metafísico, emana de Dios y no del hombre. Pero en tanto que la metafísica procede completamente de la intuición intelectual, la religión procede de la Revelación. Ésta, la Revelación, es la Palabra de Dios en tanto en cuanto Él se dirige a sus criaturas, mientras que la intuición intelectual es una participación directa y activa en el Conocimiento divino, y no una participación indirecta y pasiva como es la fe. En otros términos: en la intuición intelectual no es el individuo en tanto tal quien conoce, sino en tanto que, en su esencia profunda, él no es distinto de su Principio divino; también la certidumbre metafísica es absoluta en razón de la identidad entre el conocedor y lo conocido en el Intelecto. Si está permitido poner un ejemplo de orden sensible para ilustrar la diferencia entre los conocimientos metafísico y teológico, podemos decir que el primero, que llamaremos "esotérico" cuando se manifieste mediante un simbolismo religioso, tiene conciencia de la esencia incolora de la luz y de su carácter de pura luminosidad; tal creencia religiosa, por el contrario, admitirá que la luz es roja y no verde, mientras que otra creencia afirmará lo contrario. Las dos tendrán razón en tanto ambas distinguen la luz de la oscuridad, pero no la tendrán en tanto la identifican con tal o cual color. Mediante este ejemplo tan rudimentario, queremos mostrar que el punto de vista teológico o dogmático, por el hecho de que se funda, en el espíritu de los creyentes, sobre una revelación y no sobre un conocimiento accesible a cada uno –cosa, por otro lado, irrealizable para una gran parte de la colectividad humana- confunde necesariamente el símbolo o la forma con la Verdad desnuda y supraformal, mientras que la metafísica, que no se puede asimilar a un "punto de vista" más que de una manera enteramente provisional, podrá servirse del mismo símbolo o de la misma forma a título de medio de expresión, pero sin ignorar su relatividad. Es por esto por lo que cada una de las grandes religiones intrínsecamente ortodoxas, por sus dogmas, sus ritos y sus demás símbolos, puede servir de medio de expresión a toda verdad conocida directamente por el ojo del Intelecto, órgano espiritual que el esoterismo musulmán denomina "el ojo del corazón".

Acabamos de decir que la religión traduce las verdades metafísicas o universales en lenguaje dogmático; ahora bien, si el dogma no es accesible a todos en su Verdad intrínseca, que sólo el Intelecto puede alcanzar directamente, el mismo dogma no es menos accesible por la fe, único modo de participación posible, para la gran mayoría de los hombres, en las verdades divinas. En cuanto al conocimiento intelectual que, lo hemos visto, no procede de una creencia ni de un razonamiento, sobrepasa el dogma en el sentido de que, sin contradecirlo jamás, lo penetra en su "dimensión interna", que es la verdad infinita que domina todas las formas.

A fin de ser absolutamente claros, insistiremos todavía sobre que el modo racional de conocimiento no sobrepasa el dominio de las generalidades ni alcanza por sí solo ninguna verdad trascendente; puede, sin embargo, servir de modo de expresión a un conocimiento suprarracional –es el caso de la ontología aristotélica y escolástico-, pero esto será siempre en detrimento de la integridad intelectual de la doctrina. Algunos objetarán quizá que la metafísica más pura se distingue a veces muy poco de la filosofía; que ella utiliza, como ésta, argumentaciones y, como ésta, parece llegar a conclusiones; pero esta semejanza se debe al hecho de que toda concepción, en cuanto se expresa, se reviste forzosamente de los modos el pensamiento humano, que es racional y dialéctico; lo que distingue aquí esencialmente la proposición metafísica de la proposición filosófica es que la primera es simbólica y descriptiva, en el sentido de que ella se sirve de los modos racionales como de símbolos para describir o traducir conocimientos que comportan más certidumbre que cualquier conocimiento de orden sensible, mientras que la filosofía –que por algo ha sido llamada ancilla theologiae- nunca es más que lo que ella expresa; cuando razona para resolver una duda, esto prueba precisamente que su punto de partida es una duda que quiere llegar a remontar, en tanto que, como hemos dicho ya, el punto de partida de la enunciación metafísica es siempre esencialmente una evidencia o una certidumbre, que se tratará de comunicar a aquellos que sean capaces de recibirla, por medios simbólicos o dialécticos adecuados para actualizar en ellos el conocimiento latente que portan inconscientemente, diremos también "eternamente", en sí mismos.

Tomemos, a título de ejemplo de los tres modos de pensamiento que hemos considerado, la idea de Dios. El punto de vista filosófico, cuando no niega a Dios pura y simplemente -lo que no hará sino dando a esta palabra un sentido que no tiene- intenta "probar" a Dios mediante toda clase de argumentaciones; en otros términos, este punto de vista trata de "probar" ya sea la "existencia", ya la "inexistencia" de Dios, como si la razón, que no es más que un intermediario y en modo alguno una fuente de conocimiento trascendente, pudiera "probar" cualquier cosa; por otra parte, esta pretensión de autonomía de la razón en dominios donde sólo la intuición intelectual, de una parte, y la revelación, por otra, pueden comunicar conocimientos, caracteriza el punto de vista filosófico y revela su insuficiencia. En cuanto al punto de vista teológico, no se preocupa de probar a Dios –él permite inclusive admitir que ello es imposible- sino que se funda sobre la creencia; añadamos que la fe no se reduce en absoluto a la simple creencia porque, de ser así, Cristo no hubiese hablado de la "fe que mueve montañas", pues ni qué decir tiene que la creencia religiosa no posee esta virtud. Metafísicamente, en fin, no se tratará ya ni de una "prueba" ni de "creencia", sino exclusivamente de evidencia directa, de evidencia intelectual que implica certidumbre absoluta, pero que, en el estado actual de la humanidad, no es accesible más que a una élite espiritual cada vez más restringida; ahora bien, la religión, por su naturaleza e independientemente de las veleidades de sus representantes, que pueden no tener conciencia de ellas, contiene y transmite, bajo el velo de sus símbolos dogmáticos y rituales, el Conocimiento puramente intelectual, como hemos hecho notar anteriormente.

Sin embargo, tendría uno perfecto derecho a preguntarse por qué razones humanas y cósmicas, determinadas verdades, que podemos calificar de "esotéricas" en un sentido muy general, son expuestas y explicitadas precisamente en nuestra época tan poco inclinada a las especulaciones; hay en esto, efectivamente, algo de anormal; no en el hecho de exponer estas verdades, sino en las condiciones generales de nuestra época que, marcando el fin de un gran período cíclico de la humanidad terrestre –el fin de un maha-yuga, según la terminología hindú- debe recapitular o remanifestar de una u otra manera todo lo que se encuentra incluido en el ciclo entero, de acuerdo con el adagio que dice que "los extremos se tocan", de suerte que cosas que son anormales en sí mismas pueden hacerse necesarias en razón de las condiciones apuntadas. Desde un punto de vista más individual, el de la simple oportunidad, hay que convenir que la confusión espiritual de nuestra época ha alcanzado un grado tal que los inconvenientes que, en principio, pueden resultar para algunos del contacto con las verdades de que se trata, se encuentran compensados por las ventajas que otros obtendrán de dichas verdades; por otro lado, el término "esoterismo" es muy a menudo usurpado para enmascarar ideas tan poco espirituales y tan peligrosas como es posible, y lo que se conoce de las doctrinas esotéricas es tan a menudo plagiado y deformado –aparte de que la incompatibilidad exterior y voluntariamente amplificada de las diferentes formas tradicionales arroja el más grande descrédito, en el espíritu de un gran número de nuestros contemporáneos, sobre toda tradición, sea religiosa o de cualquier otra índole- que no hay solamente ventaja, sino inclusive obligación de hacer entrever, de una parte, lo que es el esoterismo verdadero y lo que no lo es y, de otra parte, lo que constituye la solidaridad profunda y eterna de todas las formas del espíritu.

Para volver al tema principal que nos hemos propuesto tratar en este libro, insistiremos en que la unidad de las religiones no solamente no es realizable en el plano exterior, en el plano de las formas, sino que no debe siquiera ser realizada, suponiendo que fuese posible, sobre este plano, sin que las formas reveladas fuesen desprovistas de razón suficiente; y decir que son reveladas es como decir que son queridas por el Verbo divino. Al hablar de "unidad trascendente" queremos decir que la unidad de las formas religiosas debe ser realizada de una manera puramente interior y espiritual, sin ser traicionada por ninguna forma particular. Los antagonismos de estas formas no perjudican más a la Verdad una y universal que los antagonismos entre los colores opuestos o a la transmisión de la luz una e incolora, por utilizar la misma imagen que antes; y de la misma manera que todo color, por su negación de la oscuridad y su afirmación de la luz, permite encontrar el rayo que la hace visible y remontar este rayo hasta su fuente luminosa, de la misma manera toda forma, todo símbolo, toda religión, todo dogma, por su negación del error y afirmación de la Verdad, permite remontar el rayo de la Revelación, que no es otro que el del Intelecto, hasta su Manantial divino.

Prefacio del libro del mismo título, traducido por Manuel García Yiñó, Ed. Heliodoro

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario